The Long and Lonely Fight to Save a Theatre

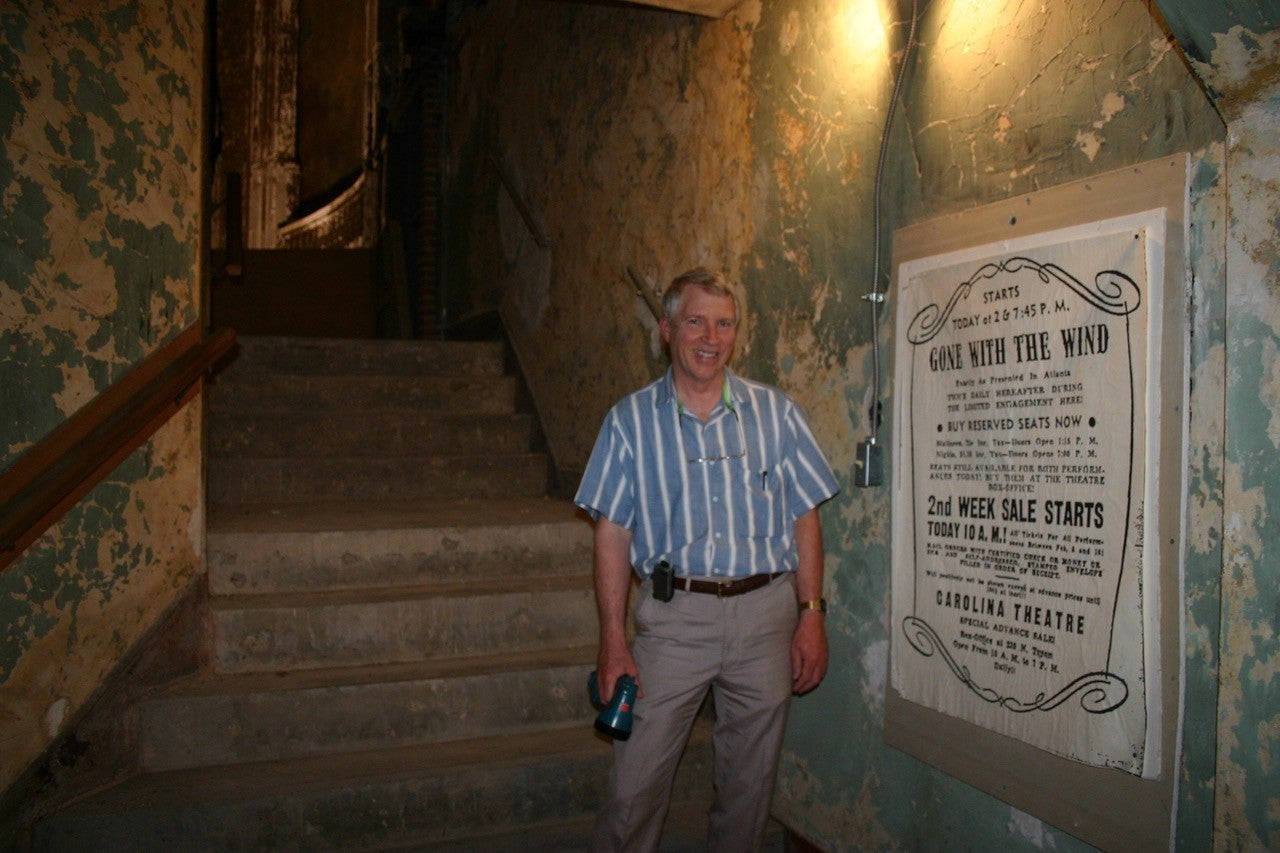

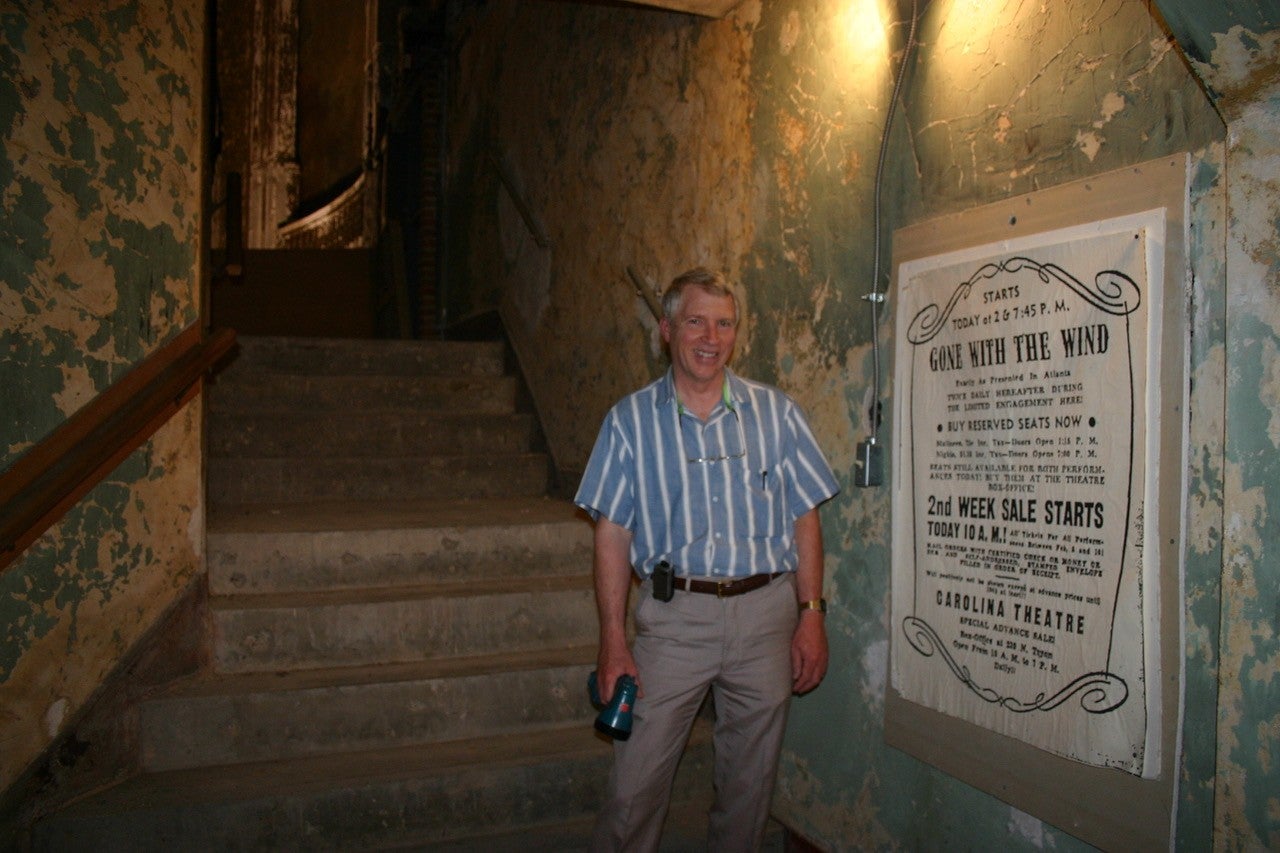

Years and years ago, before some of you were even born, Charlie Clayton would come to what was left of the old Carolina Theatre, look up and gaze around at what could have been and maybe someday would be again.

And then he’d talk to the theatre as if he knew it, as if they’d grown up together. And, in a way, they sort of did.

“I used to talk to her,” Clayton said. “I used to call her ‘Sleeping Beauty.’ I’d say, ‘We’re gonna kiss you and reawaken you.’”

Clayton is 78 now, and on a recent February afternoon, he’s standing in the newly restored Carolina Theatre, holding his life’s work – a binder full of business plans for this very theatre, structural assessments, acoustic assessments and letters of support from a hodgepodge of who’s who.

“It gives me goosebumps,” Clayton said as he looked around at the theatre he spent nearly four decades trying to save.

Looking around at the restored 906-seat Carolina Theatre with its red curtains and its silver seats glistening, it’s easy to say, “Of course we’d never raze this theatre. It’s too special to so many people.”

But it wasn’t always that way. For decades, the Carolina Theatre sat vacant, sleeping, waiting to be awakened.

* * *

Clayton was born right here in Charlotte at Presbyterian Hospital in 1946, he says, tapping the table to emphasize the year. His family moved to Atlanta when he was a child, and one of Clayton’s first memories is walking into the Fox Theatre there and feeling a sense of awe.

“All of a sudden, this music comes out of somewhere, and it was like the phoenix rising out of nowhere,” he said. “This fella is playing his organ, and it was overwhelming to my little-bitty 5-year-old brain. I was in awe.”

From then on, Clayton was hooked on historic theatres. He was even a member of the Atlanta Theatre Organ Society before he moved back to Charlotte in 1973.

But Clayton traveled constantly for work, selling complex machinery parts. He didn’t have much free time to visit Charlotte’s own historic theatre, The Carolina. He moved to Baton Rouge, La., “for a spell,” and returned to Charlotte in 1978.

But by then, the Carolina Theatre had closed its doors. He never got to visit it.

And that was that. There wasn’t much to be done. The theatre had closed, and, well, that was too bad, Clayton thought for a while.

That changed in the late 1980s when Clayton met a man named John Apple, who was also a theatre organ enthusiast. The two bonded over their desire to somehow, someway, get a theatre organ inside the old Carolina Theatre.

That was around the time when a developer planned to create City Fair where the Hearst Tower is now. The developers, Clayton said, had this plan to turn the Carolina Theatre into a nightclub. They wanted to strip it to its bones and make it flashy and new, he said. They had no interest in restoring it.

“We read about it in the paper, and we thought, ‘They’re gonna ruin this place!’” Clayton said. “We can’t let this happen. But we didn’t have control over anything.”

And here’s where he shrugs and then smiles a devilish sort of grin.

“Fortunately for us, the company ended up coming on hard times and losing their financing.”

When the developers couldn’t pay the tax bill on the parcel, the city of Charlotte took control of it, and it remained that way for many years.

But now Clayton had hope. The city controlled the theatre’s fate, and surely it would want to preserve a piece of history. In the mid-1990s, Clayton received city approval to open the theatre’s doors for the first time in years during the city’s annual Spring Fest in Uptown.

“There were no lights at that time, but people hadn’t been to the theatre in so long; they were amazed,” he said. “People didn’t even know the theatre was there!”

So more people started talking about this place called the Carolina Theatre and more people started listening to this man named Charlie who would go on and on about how we should all want to save this place a lot of people hadn’t even heard of.

And so Clayton shot for the stars and asked the North Carolina legislature for $30 million to restore the Carolina Theatre. A year or so went by, and he never heard back. Then one day, the phone rang at his office. It was someone from the state calling. We have a check for you, the person said. Where should we send it?

The state had awarded Clayton a $50,000 grant to fix up the theatre that meant so much to him. The only problem? Clayton didn’t have a nonprofit organization to accept the grant money. So in his spare time between raising children and a full-time job, he researched how to file the paperwork with the Internal Revenue Service to form a nonprofit, the Carolina Theatre Preservation Society.

“You have to be a little crazy to do this,” Clayton said, laughing. “I had a wife, two kids, dogs, cats and gerbils to take care of too!”

The city agreed to let Clayton open the Carolina Theatre to the public again at next year’s Spring Fest – but only if he could get the building up to minimum standards, meaning it needed a fire alarm and lights at the very least.

A local electric company heard about this man’s plight to save this run-down building and decided to offer its electrical services for free. Lawyers lined up to offer pro-bono work. Local accountants helped with finances. Theatre directors across the country steered Clayton throughout the process.

Suddenly, again, Clayton had hope. More than 1,000 people toured the Carolina Theatre that year.

“I brought some speakers from home and put them up in the balcony, and it was incredible,” Clayton said.

Still, opening a theatre’s doors for tours is not the same thing as fully restoring a theatre.

“We weren’t rich. We were just ordinary folks trying to make something happen. We didn’t have the power or resources that large organizations had,” Clayton said. “We were just a bunch of ragtag people who wanted the theatre to look like it does now, but no one could see that vision.”

But Clayton could see the vision, and so he persisted. He bought 250 folding metal chairs and set them up on the ground of the theatre. He bought a popcorn machine and sold bags of it for 50 cents a pop.

For several years, this is how it was. Metal folding chairs and 50-cent popcorn for small performances once every few months or whenever Clayton could find someone willing enough to perform in a sort-of open theatre. The floor was uneven. It wasn’t pretty. But it was something.

The city of Charlotte, which still retained ownership of the building, eventually took notice of the liability and forced Clayton to close the doors.

Suddenly, momentum stopped. No one was even allowed in the building anymore.

“That was a dark time,” Clayton said.

The city was interested in selling the building and getting this property off its hands. Clayton’s job was to stop that from happening. He created that big binder full of business plans and counterproposals and acoustic assessments and all kinds of reasons the city shouldn’t sell the theatre. And he gave all this research and homework to the city council members.

“I bought a really nice printer so I could print it all out for them at home,” he said, beaming.

After a while, the City Council told Clayton it liked his plan and it wanted to save the theatre, too. But where are we supposed to find the money to pay for it all?

Clayton soon became a fundraiser, trying to find partners and business prospects to pay for the theatre’s restoration. A restaurant atop the theatre never panned out, but a condo building seemed promising for years. At one point, the planned condo building had a 60% commitment rate and an elevator just for cars.

That was in 2007. The next year, the economy cratered, and everything was gone.

“A lot of people said, ‘OK, Charlie, we had a good run,’ and no one could see anything else because the ‘08 recession was so bad that no one could see past it and how we could climb our way back up,” Clayton said.

Here again, he shrugs and smiles.

“I’m just too stupid that I didn’t realize that!”

Clayton, in a last bit of hope, spoke to Michael Marsicano, then the CEO of Foundation For The Carolinas, and asked was there anything left to do? Was there any more hope to be had?

“He said, ‘Don’t worry, Charlie, it’s all gonna work out.’”

The city of Charlotte gifted the Carolina Theatre to the Foundation for $1 two years later.

As the adjacent neighbor/property owner, the Foundation had a vested interest in the site and sought to ensure the property was a complement to the surrounding neighborhood, a landmark for Tryon Street and a strong civic and entertainment destination for Uptown Charlotte.

The Foundation soon announced a $51.5 million capital campaign to launch the formal rebirth of the Carolina Theatre. As of today, the campaign has increased to more than $90 million.

The complex and careful restoration process began in 2017 and lasted eight years. The Carolina Theatre will reopen in March 2025, nearly five decades after closing its doors.

Clayton will be in attendance on day one.